Thirty-six years after its first publication, Visitants remains, in my view, the finest Australian novel that takes Papua New Guinea as its inspiration and dilemma. Set on the Trobriand Islands in 1959 and published in 1979, it is a modernist novel of a colonial moment. Between those dates, 1959, when Randolph Stow was himself in the Trobriands, and the novel’s publication in 1979, PNG went from being a Territory of Australia to an Independent State. ‘Stretch your ear to ground and listen to the distant stirrings’, goes a line from the Trobriand Islands writer John Kasaipwa- lova’s 1971 poem ‘Reluctant Flame’. In those twenty years of profound change, the voices of Papua New Guineans, muted in 1959, audible only to those with ears to hear them, had become loud and insistent. As an epigraph for Visitants Stow chose this line from The Tempest: ‘Be not afeard; the isle is full of noises…’

I have read this novel many times, and with growing admiration. Having written about PNG myself, though not until much later than Stow, I know how hard it can be to do justice to a place that lives by different concepts and understandings of the social universe—different, that is, from those of us white visitors who travel there and find ourselves profoundly affected by its strangeness and its power. Stow was certainly that, his months in the Trobriands as a young man leaving lasting damage that was in part exorcised in Visitants. (The story of his time on those islands will be told in Suzanne Falkiner’s forthcoming biography of Stow.)

My interest in and admiration for Visitants lies in the rigour and brilliance of its form. It is a novel of voices—echoes, rumours, languages understood and misunderstood—given to us with no controlling narrator. We must come to understand the complex narrative of intersecting plots through the pattern of voices, half Dimdim—as white people are called in that part of Papua—and half Kiriwina, as they weave back and forth, among, around and against each other.

Stow doesn’t do what so many novels of PNG do, mine included, which is to resort to ethnographic asides and explanation. The colonial voices show us the deafness of those who cannot hear the distant stirrings, but for us as readers to comprehend them we must listen carefully to the Kiriwina voices, as each speaks from the perspective of its own perceptions of what it takes as normal. This, to my mind, is the radical achievement of Visitants, for it not only turns the colonial gaze back on itself, the view from the ‘other’—the blundering white man in the tropics, a not-unfamiliar trope—but it incorporates into the text the language, the patterns of syntax and expression of the Kiriwina language.

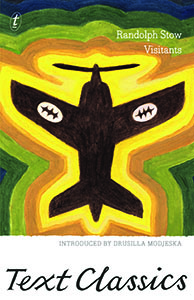

So, who are the visitants? Well, they come in many forms, and the title itself situates us with the Kiriwina; while the patrol officers, or kiaps, and the planters don’t regard them- selves as visitants, that is what they are, part of a long history of sailors and traders, kiaps and missionaries, coming and going. More dramatically, the visitants are the figures which appear—or are rumoured to have appeared—in a strange object that hovers in the sky, some sort of ‘star-machine’. The novel, with its voices, is followed by a short note signed R.S. about the incident recorded in the prologue, the sighting in June 1959 of a ‘sparkling object “very, very bright”’ which appeared in the sky and came close enough to the earth for a missionary (‘himself a visitant of thirteen years standing’) and ‘thirty-seven witnesses of another colour’ to make out the figures inside. The note states that this incident, or the record of it, is not fictitious and is incorporated into the novel ‘without comment’.

The ‘witnesses’ of Visitants, five of the voices, are, ostensibly, witness to a colonial-government inquiry into the suicide of Patrol Officer Alistair Cawdor while on patrol on one of the outer islands, Kailuna. Entangled in the story of Cawdor’s suicide is the story of the conflict on the island over who will inherit ‘command [of] the villages’ from the old chief, Dipapa. Entangled in that story, and in Cawdor’s suicide, is the mystery, the rumours, of the flying object, that in turn become entangled in millenarian hopes, beliefs and partially suppressed cargo cults that erupt into violence at the end of the novel. As Anthony J. Hassall puts it in his 1986 study of Stow, Strange Country, the official government inquiry is the conceit; the novelistic achievement is the rendering of the voices that invites an understanding, a way of seeing these entangled threads, entangled lives—which the colonial inquiry will prove incapable of.

Randolph Stow was himself a visitant. For five months of 1959, aged 23, he was in the Trobriand Islands as a Cadet Patrol Officer and an assistant to the Government Anthropologist, sent there to investigate a situation—feared destabilising by the colonial administration—that had to do with the ageing chief. ‘He has two heirs-apparent already,’ Stow wrote in a letter to Geoffrey Dutton, and has cut them off for going to bed with his wives (he has thirteen) and now he announces that the chieftainship is going to die with him. Après moi le déluge. He’s a perfect example of…the indifference of old age, and at the same time its passionate, pig-headed desires.

In Visitants there are two pig-headed old men: Dipapa, the chief, and MacDonnell, the planter, who have co-existed for decades in an uneasy balance of rivalry and alliance—and, when we meet them, are each resisting not only their own passing and each other, but what they fear will come after, beyond their control. As the assistant anthropologist, or ‘legend man’, Stow’s role was to collect oral histories of the disputes and (mostly quiescent) cargo cults they were there to assess. Able with languages, he could soon converse in Kiriwina, which was essential if he was not to rely on everything being mediated by the Government Interpreter. Much of this experience finds its way into the novel. Dipapa, the fictional chief, with his slow dignified walk; young Saliba, with her ‘boiling skirt’; MacDonnell, the fictional planter, with Sexual Deviations on his shelf: such detail is a gift to a novelist.

Trickier to deal with is the question of how to use profoundly different cultural understandings. In unpublished notes of his time in the Trobriands, Stow records a group of men trying to figure out what the bright, hovering object could be. Was the war with Japan in fact over, they wanted to know, or could it be the Japanese returning? ‘It is a tragicomic business,’ Stow wrote,

and the temptation, especially for a writer of fiction, is to emphasise the comic elements and to treat the cultists as a crowd of savage idiots. But we Dimdims are by no means always rational in “spiritual” matters.

In the novel, the rooky kiap Dalwood calls Cawdor crazy for taking the sightings seriously. ‘My father…believes that Jesus Christ was the son of God,’ Cawdor replies. ‘Boy, is he crazy, but no one says so.’ Stow brings us Dimdim readers to see that maybe the idea is not so crazy, not so much by exchanges like that, but by weaving into the text, before the rumours start, all manner of star sightings: the star of Bethlehem in Mission stories, the bullets and ammu- nition that fell from the sky in the war and went ‘bang in their faces’. Lamps, lights, torches, fires, fireflies: the sky is a tableau of stars. Why not star-people?

In one of Cawdor’s longer diary extracts, he reflects on the ‘receptiveness’ of the islands, with everything incorporated into the Kiriwina social universe, that ‘comforting institution, that scheme of things’: vast stretches of time, volcanoes rising from the sea, lagoons rejoining the ocean, gardens growing, clans forming, a rich world with the Kiriwina at its centre, ‘digesting’ a parade of visitors since the French explorer D’Entrecasteaux at the end of the eighteenth century.

‘Black men, white men,’ the old chief says, ‘canoes, steamers. They bring their somethings. But we—we stay and watch, that is all. Every day the same.’

But is that the view of Benoni, his nephew, the young contender? He might think, hope, that colonial rule will pass, but he’s worked at the naval base on Manus; he speaks pidgin; he’s seen the technology, the money, the power of modernity. It is Benoni who, in the novel, asks the question about the Japanese, not because he doesn’t know—for he does; he asks because he wants the men of the village who ask him that question to hear his answer corroborated by the Dimdims.

This is one small move in Benoni’s play of power and knowledge against the old chief. He knows there’s no going back to a past that in any case was always changing, shifting, digesting. No, the villages won’t remain ‘the same’. Benoni doesn’t want ‘same’; he wants to influence, mould how the social universe of the islands will meet the challenge, the threat, the dilemma, the possibilities ahead. Colonialism will pass, but not modernity.

*

One reading of Dipapa’s rage near the end of Visitants is that the really frightening visitants are not the ones that come in steamers, or appear from the sky and go away again, but those that take up lodging within us: the lodging of the new ways in the new generation. What has lodged in Benoni; what visitant will reign if he is not prevented from becoming chief? Sleeping with Dipapa’s young wife is shaming, but is it enough to trigger the destruction of the villages?

And what has lodged in Patrol Officer Cawdor? We know he has malaria in the days before his suicide. What other visitant has lodged in him? ‘It is like my body is a house,’ he is reported to have said right at the end, ‘and some visitor has come and attacked the person who lived there.’ We know his wife has run off with the Government Doctor; we know he is shamed; we also know he was not at ease in the colonial social world he inhabited with her. Osana, the Government Interpreter, might hate the way his power is diluted by Cawdor’s fluency with Kiriwina, but it is Cawdor’s understanding of the island, his ability to hear the island’s voices, that Benoni responds to, and uses, in his struggle to depose Dipapa.

Benoni understood who Cawdor was, but for others on the island the question remained: had this strange, unnatural kiap who chewed betel and smoked trade-store tobacco somehow crossed into territory where he did not belong? Was he a visitant, or was he not? Was the visitant within him? Or had he, to put it in Dimdim language, ‘gone troppo’, that’s all?

That is the conclusion of the Assistant District Officer presiding over the inquiry. He misses just about everything, understanding little or nothing of the events culminating not only in the suicide of Cawdor but the burning of the villages and the death of Dipapa. He does not see Benoni’s role, but at least in the case of a young man—a future ‘native District Commissioner’, maybe—he sees that Benoni could have been a player. When it comes to Saliba, the major female voice in the novel, he sees only ‘a domestic in MacDonnell’s household’. The question of her role simply doesn’t arise. Naibusi, the old woman who is a great deal more than MacDonnell’s ‘housekeeper’, doesn’t even get called as a witness to his inquiry.

Yet on this matrilineal island, it is these two women, one young, one old, who know exactly how these narratives intersect. Both are snared in the changes and upheavals stir- ring the islands; both are critical to the outcome. It is we, the readers of the novelistic inquiry, who come to understand that women, and especially older women, are essential to the stability of the Kiriwina social universe; their power is very different, but no less significant, than that of the chief. Of the Dimdim men, it is Cawdor who sees, or suspects, what has happened. There are clues in his diaries, but these do not sway the ADO. Cawdor had ‘gone native’, after all; ‘gone troppo’. If MacDonnell and Dipapa represent the old men, the old way, the uneasy colonial balance that must, and will, pass, then Cawdor and Benoni, along with Saliba, are of the generation that has been formed, and caught, in the profound changes and cultural crossings that had come to the islands and to PNG by 1979. A modernist novel of a colonial moment, as I say, told with a postcolonial mind. But must the cultural crossings always be so tragic?

This is a large question, for which Visitants has no easy answer.

Cawdor dies an ugly death. Stow does not spare us the detail, and there is nothing to be said in mitigation. And yet. On the night before his suicide, Cawdor gives Dalwood a copy of the book he’s been reading, William H. Prescott’s The Conquest of Mexico; inside, he has written in the Kiriwina language:

Do not be sorry. Everything will be good, yes, everything will be good, yes, every kind of thing will be good.

This, to the ADO, presiding over the inquiry, confirms Cawdor’s ‘confusion of mind’. In his report he adds that a priest on the island ‘believes this note contains a quotation from English’. Which of course it does, with its echoes of Julian of Norwich, and T. S. Eliot, a mystic, poetic inheritance of which this colonial arbiter is unaware. We also know that these are words that Naibusi has used both to Cawdor and to Saliba. The Kiriwina world, she is saying, will be well. It is more than any of them. ‘You will see, how all will be well.’

But will it? There are powerful forces at play, and none of the witnesses, except perhaps MacDonnell, believes that the matter is ‘ended’, as the ADO tells them—for clearly it has not.

This is Drusilla Modjeska’s introduction to the Text Classics edition of Randolph Stow’s Visitants, published on 26 August 2015.