A friend suggested I apply for the job of editor at Penguin Books in 1982. I had a bit of experience at the Publications Section (not MUP) at Melbourne University ten years before and was currently working with Correct Line Graphics (the gay layout, design and typesetting enterprise which produced among other things Gay Community News and books for Sybylla Press, the feminist publisher). It was not an auspicious CV to front with at an interview with the Penguin publishing director, Brian Johns, his senior editor, Jackie Yowell and editor, Carla Taines.

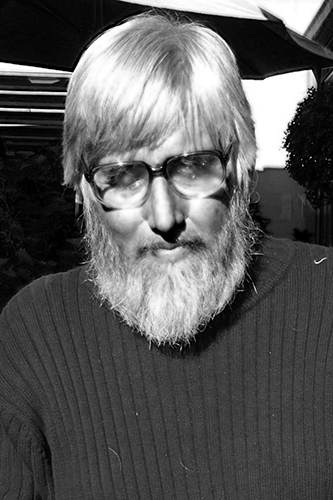

The interview was a bit like walking through puddles, as each clearly had a different agenda. The crunch came when Brian said, ‘We’re looking for someone who’s likely to stay a few years.’ Feeling cheeky, I said, ‘So you’re guaranteeing a job for a few years?’ ‘Oh,’ said Brian a bit sheepishly, ‘I see what you mean.’ I doubt that I would have got away with that with many other people.

As I left the building escorted by Peg McColl (more about her later), she asked whether I could type. If I couldn’t she would have had to type my letters. I said I could and I suspect that contributed to me getting the job.

Penguin was then in Ringwood which seemed the end of the earth but it had a well-designed pleasant building with a bush garden at the front, a couple of sculptures and two fish ponds. Brian was famous for lunches and at Ringwood there were not many options. Daisy’s, part of the Ringwood pub, did old-fashioned pub lunches. At one of them, Di Gribble delighted in the fact that you could get lamb’s fry, then unobtainable in trendy Fitzroy. Not that Hilary McPhee or Di often came to Ringwood. Brian preferred to meet them on their home territory for a drink on Friday afternoons followed by a meal at which Carlton agent John Timlin once pontificated that ‘publishing was a cottage industry’. Indeed it is and proud of it.

In Brian’s early days, the whole department was small enough to go to lunch. At one of these lunches, the discussion turned to favourite books. Peg McColl, not long on the staff, said she liked Colleen McCullough. A quiet snigger went round and Brian fixed the group with his genial but gimlet stare: ‘If any of you can bring me a book that sells as well as her, I’ll be well pleased.’

Brian hated formal meetings and written proposals of more than one page but loved conversation. The pub meetings were very productive, though sometimes lengthy. The editing and design staff earned disapproving looks from the then Sales and Marketing Director, Peter Field, as we passed his office on the way back into the building. We might or might not have been over the limit on the way home, but those days were more forgiving. Other things were very different. Brian used to call one of the women staff, ‘the old boiler’ (she wasn’t) or others ‘sheilas’. He always resisted token political correctness, but his regard for the intellect and competence of women – whether work mates, fellow publishers, journalists or writers – was marked and still quite unusual at that time.

There are those who say that Brian was not good at business, perhaps because his shirt often hung out over his trousers long before it was fashionable. Not at all. His eye was focussed very much on the bottom line. A few years ago, I was part of a research study by Ivor Indyk at University of Western Sydney. Among the things I discovered was that during Brian’s time at Penguin, Australian publishing actually made money, particularly through literary fiction, a notoriously difficult genre to make pay. Interestingly, his successor, Bob Sessions, also made money but more through non-fiction and children’s.

In the annual consultations about wages, Brian was good at keeping a lid on expenses and was never lavish in the giving of large advances to authors, preferring to outlay money that had at least a fair chance of being earned back through sales.

He worked very closely with the late, genial and gentlemanly Trevor Glover, then managing director of Penguin. Brian was not, as often reported, the head of Penguin. Trevor was the boss but left the publishing decisions to Brian except when he needed to be consulted on very large expenditure. Trevor refused to allow what was then called Personnel now HR into Penguin, preferring managers to handle their own staff issues. Another very decent man, John Strike, was the company secretary. His accountant’s limits were stretched when Brian negotiated a deal with Frank Hardy for a book which needed to be paid in cash into Hardy’s TAB account.

There was a cut-throat weekly meeting at Penguin called the Price Meeting at which print runs and prices for new books were decided. One of the few women participants described the meeting ‘a whole lot of blokes sitting around and flopping their dicks on the table’. It was the chance that the rest of the company had to meddle in Brian’s publishing program, though he could usually get what he wanted by force of personality. He later said after the deal to co-publish with McPhee Gribble that he was given the power to decide on the quantities and prices of their books, a power which he didn’t have for his own, one of the many anomalies in that peculiar arrangement.

Anyone in the publishing department, or indeed the whole company, could put forward a publishing idea. Brian would always ask, ‘How many and how much?’. His was focussed on both the reality of sales and the pragmatic notion of the reader. He did not believe in the abstract notion of ‘pure’ editing, but of editing for a market. He had this in common with managing editor, later associate publisher, Jackie Yowell, who provided him with much publishing nous and drove the publishing program in both its entirety and the very demanding job of getting books completed in a rapidly expanding list. Everyone worked very hard and productivity was high, again helping the bottom line. Resources always lagged behind output.

While Penguin always had very efficient marketing and sales departments, an essential for a successful publishing machine, Brian through his vast network of contacts could not only tap into potential authors but also do his own very personal brand of marketing by ‘talking his books up’ in influential places.

However many friends and contacts he had in high places, Brian kept his feet firmly on the ground. A friend told me that when he arrived at the ABC he visited all program areas to meet people and find out what they did. No MD before or since has done this. At Penguin, he would give staff a chance based on their talents and initiative. I certainly benefited from this as did Peg McColl and Julie Watts. Peg, who started at Penguin doing photocopying, became the contracts, rights and permissions manager. After 35 years in the job, she probably knew more about the complexities of the area than anyone in Australia, including literary agents and lawyers. Julie, who came to Penguin after being a dogsbody at the early McPhee Gribble, became Australia’s most respected children’s publisher with notable successes in other areas like fiction and Li Cunxin’s Mao’s Last Dancer.

She recalls Brian thundering down the corridor in the morning jangling his car keys, having come into the building through the warehouse to find out which books were moving out and which returning. Behind his office door was a collection of ties in the unlikely event of a VIP dropping in to Ringwood. She also remembers being surprised as a lowly ‘typist’ when she was invited to lunch and had her opinion valued. Brian put all of us on the spot by asking what we had been doing and what we had been reading. For Julie, it became a process of learning to trust her instincts. She says that without Brian and the rest of his team she would not be the person she is today.

Brian’s major passion was what he called ‘mapping the culture’. He published a hugely eclectic list with non-fiction which centred around politics but also included a lot of art including the ground-breaking Rebels and Precursors by Richard Haese, brilliantly designed by George Dale. Brian persuaded Blanche d’Alpuget to publish her novel Turtle Beach straight into paperback breaking a longstanding publishing tradition of first publishing into hardback. It sold very well and started a trend which has lasted.

He was concerned to lead the debate on issues and publish more quickly than traditional publishing allowed. An early success was The Boat People by Bruce Grant which influenced the debate over Vietnamese refugees. The scope was broad across history, economics, politics, Aboriginal affairs, domestic violence, art, architecture, alternative health, religion and much more. He was also determined that Penguin’s Australian publishing would be central to the company, not a self-indulgent add-on.

He said that a cover is like a poster for the book. The design team worked minor miracles. David Ireland didn’t like the sexy cover for Woman of the Future but changed his mind when sales went through the roof. Brian’s instincts for marketing and feeling for what the Australian public wants have carried on into all his subsequent jobs.

The children’s list grew and prospered, first under Kay Ronai, then under Julie Watts. Many authors got a start from their desks including Paul Jennings, Isobelle Carmody, Sonya Hartnett and Melina Marchetta.

Fiction was a great love for Brian and he had a good eye for it. Jane Arms, who had worked with the previous Penguin publisher, John Hooker, freelance edited a number of books for Brian and worked wonders with authors to bring out the best of their books as did the other Penguin editors.

Ever with an eye to a quid, Brian bought the paperback rights to A Fortunate Life from Fremantle Arts Centre Press and it sold hugely through Penguin’s efficient distribution. Later, both Fremantle and University of Queensland Press would have distribution arrangements with Penguin.

These deals are always a bit fraught as the ‘agencies’ always feel they are not getting as vigorous a treatment from the sales team as the publisher’s own books whether they are or not. The reality is that authors with a track record get more push from the sales team than first-time authors. Brian would often have drinks with the sales reps when they arrived back at base at the end of the week to get feedback on what was selling and to spruik his latest books, then head off to Carlton and Fitzroy to the inner-city literary scene. He was an inexhaustible talker and listener.

Brian and Trevor negotiated an arrangement with McPhee Gribble which was controversial from the start. It was designed to boost Brian’s Australian list with McPhee/Gribble Penguins and help both companies’ cash flows. In the end, after Brian and Trevor left, Penguin made a lot of money out of McPhee Gribble which it bought outright.

The other expansion was acquisition of the Lloyd O’Neil group of companies which purchase included Robert Sessions Publishing and a list with a different flavour from the traditional Penguin books: illustrated non-fiction, cooking and cartography. It added a breadth to the list as well as a talented crew of publishers, editors and designers.

I sat in on many of the meetings with Lloyd, Bob, Hilary and Di. Brian was impressive for his grasp of realpolitik, hunger for ideas and real gift for looking at people and seeing them for what they were, not what their status was. Add to that a very good eye for business and the bottom line.

A source of frustration for Brian was in the area of overseas sales. Being part of the Penguin international group had advantages and hazards. While the overseas Penguin companies were willing to take a quantity of some Australian titles, it was never enough to give the authors a real presence in the UK or US markets which a proper rights deal would have given. For some established authors, the Penguin group was an advantage, for example keeping Patrick White, Randolph Stow or David Malouf’s books in print internationally, but a new author had difficulty getting established. In many ways, this was an inevitable outcome of being an outpost at the edge of the world. For Brian, this was a part of a game of keeping many balls in the air at once. In visiting the metropolitan centres, the difference between the condescension of the British and the false friendliness of the Yanks was not very much. The fellow feeling came from the Canadians and the New Zealanders.

When Trevor Glover answered the call to a job in head office in the UK, his job as MD went to Peter Field. Not long after, in 1987, Brian got the job of MD at SBS, a role for which he was eminently suited. The publishing staff were devastated. Brian, our friend, mentor and inspiration was going. As he said, years later, ‘What good, happy days they were. In a way they have never gone away because I learned what can be done. We were all learning together – doing new things.’