In my idle moments this week I have been reading the most recent book by the liberal philosopher Martha C. Nussbaum, Political Emotions: Why Love Matters for Justice (2013). In Political Emotions, Nussbaum takes up a central dilemma of liberal political theory – namely, how a nation that values and seeks to preserve the principles of pluralism and individual freedom might, at the same time, maintain a stable, inclusive, cohesive society. This is a fundamental issue that can be traced back to the origins of modern political thought in the work of Locke, Kant and Rousseau, and which has exercised later liberal thinkers, such as John Stuart Mill and John Rawls. It is also an issue that is unresolvable, strictly speaking, since the ideal that a liberal democratic society sets for itself is to realise a state in which justice and power coincide. This is something that can only ever be achieved imperfectly because power, by definition, means having the ability to enforce one’s will whether or not one is in the right.

Political Emotions attempts that delicate balancing act which seeks to reconcile the worthy ideals of equality and inclusion to a complicated reality, and to be realistic about the difficulty of doing this without lapsing into cynicism. As Nussbaum recognises, this basic underlying problem for liberal political theory inevitably leads it into the murky realms of human psychology and somewhat nebulous abstractions about collective sentiment. She suggests that the difficult issue that much liberal thought has not adequately addressed is how to encourage beneficial public emotions without undue coercion. She argues that we need to take full account of what Kant called ‘radical evil’ – which, despite the sensational-sounding terminology, merely refers to that ineradicable human impulse toward what Nussbaum summarises as ‘competitive self-love, which manifests itself whenever human beings are in a group’ – and, beyond that, to account for the prevalence and influence of various other regressive sentiments: ‘racial and ethnic hatred, the desire to denigrate and humiliate, the love of cruelty for its own sake’.

Nussbaum’s arguments are far too intricate and wide-ranging to elaborate here, but one of their side-effects is to serve as a reminder of the shallowness of much of the lofty rhetoric about freedom of speech that we have been subjected to in recent times, mostly about how we don’t have enough of it, much of it under the banner of a modish ‘libertarianism’. It has been suggested that it is an intolerable restriction on freedom of speech that a privileged white man cannot make free use of a racist epithet; it has been argued that reform is needed so that a man might be free to attack in print a group of people on the basis of their race, even if that attack is found to be in bad faith and factually inaccurate; we have been informed that bigotry is a right. In a week that saw the kinds of destructive political emotions that Nussbaum identifies – fear, disgust, contempt – reclaim their place at the centre of the national conversation (they never seem to be too far away), a week in which all the talk was suddenly about limiting freedoms and enhancing powers and increasing surveillance, it certainly didn’t seem to be the case that anyone’s right to be a bigot was being unduly curtailed. Quite the contrary, it was being enthusiastically exercised by a number of our elected representatives. It’s ‘Banned Book Week’, incidentally.

Almost invariably, arguments such as Nussbaum’s look to cultural forms (arts of various kinds, rituals, spectacle), investing them with a quasi-religious function that connects them to a civic purpose – if not exactly as a means of encouraging civic virtue in a narrowly instrumental sense, then at least as a manifestation of our better natures, or as an open-ended creative space in which other perspectives might be encountered, marginalisation and stigmatisation might be called into question, and empathy might (just might) be encouraged. Art can be enlarging; it can make mutual understanding at least seem possible, even if this understanding turns out to be precarious, if not illusory. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Nussbaum’s book is her consideration of cultural forms as means of collective expression, as distinct from an applied means of encouraging right thinking.

It remains a precious, precarious and perhaps ultimately unaccountable argument. The precise connection between affect and social effect is difficult if not impossible to establish with any certainty. Yet the idea has a durability that derives from its kernel of truth. A work of art – an excellent work of fiction, for example – does move us; it has at least the potential to make us see things differently. It can give us pause, it can force us to think, it can lead us to make connections that we might not otherwise have made. This is part of the argument Michelle Cahill puts forward in her review of The Secret Maker of the World, the latest fiction collection from Sydney-based writer Abbas El-Zein. ‘El-Zein shatters familiar representations of the Arab world,’ writes Cahill, ‘restoring its subjectivity in the intimate perspectives of his stories.’ His fiction is a world of exiles and marginalised voices. It is full of vivid and unexpected depictions that ‘break down the distancing effect of historical inquiries, policies and polemics, and the dominant vocabularies used to describe the Arab world’. And it raises timely questions: ‘Who is perpetuating terror? Who are the victims? Who is a threat to security within the global contexts of the war on terrorism and fundamentalism?’

Our second essay this week is Susan Lever’s consideration of Bark, the most recent book from another excellent short story writer, Lorrie Moore. In ‘To wit’, Lever argues that the events of September 11, 2001, have left their mark on Moore’s fiction. While Moore’s trademark humour is strong in her latest work, there is evident throughout a thematic alignment of domestic and political concerns. Nevertheless, in the course of her appreciative and thoughtful consideration of Moore’s art, Lever raises the question of the constraints of Moore’s familiar subject matter, her remaining closely aligned to a narrow range of settings and subjects, which ‘raises the possibility that her working life may have not only limited the quantity of her output, but has also confined her material and her style’.

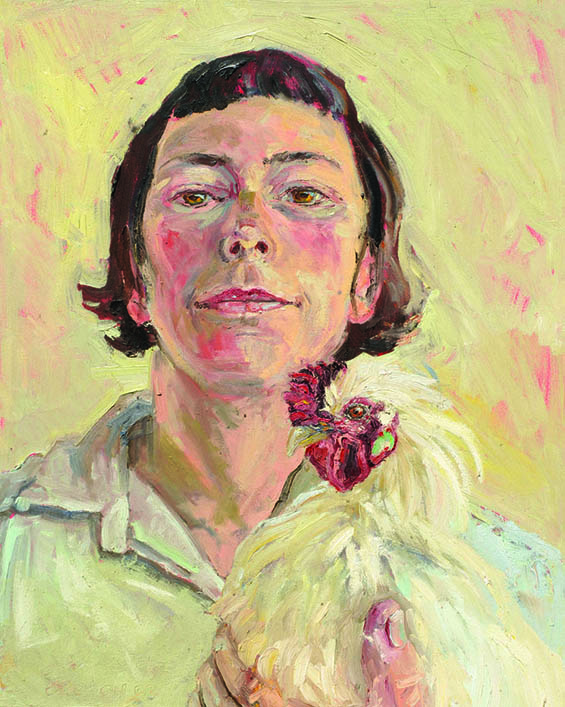

From the Archives this week continues the short story theme with Tegan Bennett Daylight’s ‘The Worst That Could Happen’, her excellent review from last year of George Saunders’s award-winning collection Tenth of December. Our image is Lucy Culliton’s Self with Cock, (2005) from the exhibition ‘Eye Of the Beholder: The Art of Lucy Culliton, A Survey Show’, which is being displayed from 20 September – 30 November 2014 at the Mosman Art Gallery.